A basic element in the Compressed Air Challenge® (CAC) philosophy is that compressed air system optimization should be addressed using the “Systems Approach”. This method recognizes that improving and maintaining peak compressed air system performance requires addressing both the supply and the demand sides of a system and understanding how the two interact. “The road to energy efficiency involves more than just fixing the leaks,” says Ross Orr, an experienced auditor with Scales Industrial Technologies and a certified CAC instructor, “If you don’t investigate the rest of the system, then you leave a lot of money on the table. We have seen instances where addressing an inappropriate use of compressed air cut the total system demand by more than half. A very important step in planning a new compressed air system, or upgrading an existing system, is to look closely at how compressed air is used.”

“One of the biggest issues preventing most plants from maximizing their compressed air system's efficiency is understanding it is a system – not just compressors and some piping.” Explains David Booth, another CAC certified instructor and Sullair’s lead auditor/trainer, “ In most cases if you ask a plant to show you their compressed air system they take you to the compressor room, but that's just one part – the supply side. Few are able to even identify their largest or most critical end users – the demand side. Fewer still know these end users' actual requirements – pressure, flow and air quality. The CAC fundamentals course does a nice job introducing these concepts by providing some basic knowledge on the components and then building on them to get participants thinking about not just how they produce air, but how they actually use it. It really makes them think about the whole system.”

The investigation of the demand side involves breaking the system down into “end uses” and assessing the characteristics of these elements. In this way, proper planning of efficiency and other system improvement measures can be done without negatively affecting the system.

“Too often facility managers just want to buy a new compressor and think that will solve all their energy efficiency woes.”, says Orr, “Quite often we find even new compressors that are inefficient at part load or a system with a control strategy that cannot efficiently react to this new lower system demand without some modifications.”

“When you can step back and take a systems approach and start analyzing the compressed air system as a whole, you start to see what is reasonable and efficient for the whole plant and not just one component or one user,” explains Booth, “Often a plant will specify and spend more money on a compressor just because it is 1 to 2 percent more efficient at some rated full load condition. But that same plant may be adding 10 to 20 percent to their annual costs because of unnecessarily elevated pressures or wasting 30 to 40 percent of their compressed air in leaks or driving equipment that should not be powered by compressed air.”

How Much Compressed Air is Needed?

The CAC’s Best Practices Manual discusses end use analysis in several sections and is a very good reference to use to assist in studying your system. The following is an excerpt of Section 1 “The Demand Side – How to Analyze New and Existing compressed air systems” from “Best Practices for Compressed Air Systems”. This 325 page manual is available at our bookstore.

1. What is the use?

Each industry is different and each plant within any given industry is unique. A new plant will have specific initial requirements, but these will change over time and anticipated growth should be considered in the initial design.

- Identify and tabulate anticipated end uses and quantify rate of flow compressed air requirements.

- Machinery and processes requiring compressed air should be identified by type and the manufacturer’s specified air flow requirements noted.

- General use plant air also should be identified and quantified.

2. What is the True (or actual) Air Requirement?

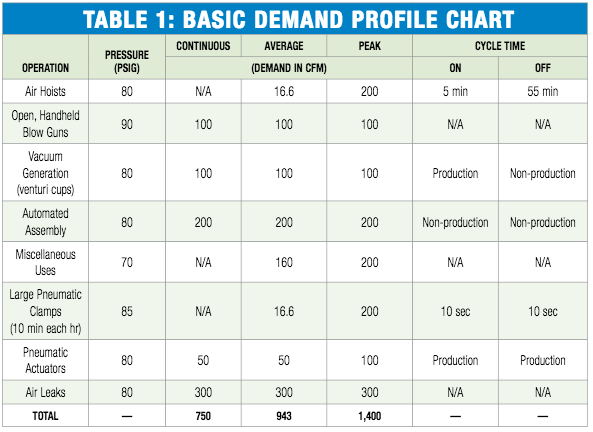

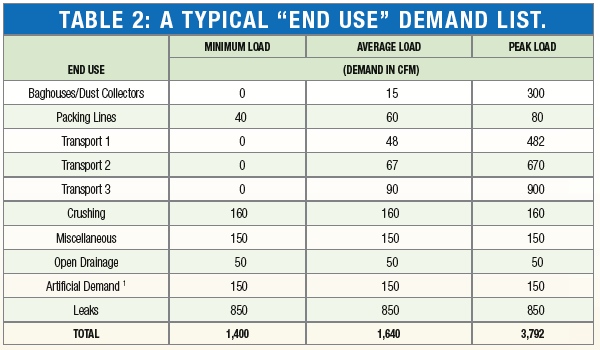

- List each by type, using a table similar to the Table 1: Basic Demand Flow Chart and the tables in appearing in the Best Practices manual, which also show typical uses of compressed air.

- Identify alternatives to any potentially inappropriate uses. (See Fact Sheet 2 at http://www.compressedairchallenge.org/library/factsheets/factsheet02.pdf)

- Identify steady or intermittent demand.

- Check number of shifts and resulting variations.

Use equipment manufacturer’s specifications for:

- Average flow rate requirement.

- Maximum flow rate requirement.

- Minimum pressure requirement (challenge the stated requirement).

- Maximum pressure requirement. (Is there a built-in pressure regulator?)

- Air quality requirement, (e.g. oil free, degree of dryness and filtration.)

- Note the locations – groupings or scattered.

- Estimate potential future additions.

- Estimate total air flow and best and worst case scenarios. (Include provision for leaks)

- Develop a Demand Profile Chart.

- Shut off air to any application not in use.

- Determine the range of pressure requirements. Should some be segregated?

- Determine if oil free applications should be segregated or should all be oil free?

- Determine maintenance needs.

Each end use should be compared with alternatives and justified.

3. Why the use?

Not all uses of compressed air are appropriate, or efficient, but in some cases may offer a better alternative. (Refer to the Potential Inappropriate End Uses.)

4. How to Develop a Demand Profile Chart

Misapplication of compressed air at the end use is very common and results in the system operating inefficiently. A demand profile chart can assist in identifying applications that lead to poor system performance, excessive energy costs, and increasing maintenance and repair expenses. Minimum, average and peak rates of flow, combined with on-off cycle times, are important criteria.

The demand profile chart will provide the information for an overview of the system to determine the actual end-use requirements. For a new plant the chart is a compilation of the data required to select the total compressor capacity and the system operating pressure. This data should be provided by the manufacturers of the end-use equipment.

For an existing plant, an analysis of the data can assist in determining where system inefficiencies exist or where there may be opportunities for improvement. For example, an end use with small air consumption can cause the entire system to operate at elevated pressure. Determine if the application can be modified to operate at a lower pressure or if it should be segregated to allow the main system to operate at a lower pressure. For an intermittent high volume use, additional storage may avoid the need to continually operate compressors inefficiently at partial load merely to meet an occasional peak requirement. Table 1 shows a typical demand profile chart. End use equipment is often added or modified, so you should update the chart periodically so that it remains current.

Notes:

- In some end uses, the minimum flow rate may be very low or zero (cycle time - off) until an intermittent operation (demand event) occurs, when there is a large demand (peak flow rate) for a given period of time (cycle time – on). The combination of these will determine the average rate of flow).

- End uses having a steady rate of demand can be identified only with the average flow rate.

- Peak flow events may require additional primary storage and/or secondary storage to maintain stable system pressures. (Rate of flow issues for end use applications are covered in detail in the CAC’s Best Practices Manual)

- When preparing a Demand Profile, pressures also should be considered, since not all end-use applications require the same pressure.

Note: there is much more information in the BPM discussing the following items:

- Number of shifts and resulting variations

- Average and maximum flow requirements

- When is the use (and when not)

- What about leaks?

- What is the future?

- What pressure is needed and why?

- Where is the use?

To obtain your own copy of the Best Practices Manual visit www.compressedairchallenge.org

Final words from David Booth:

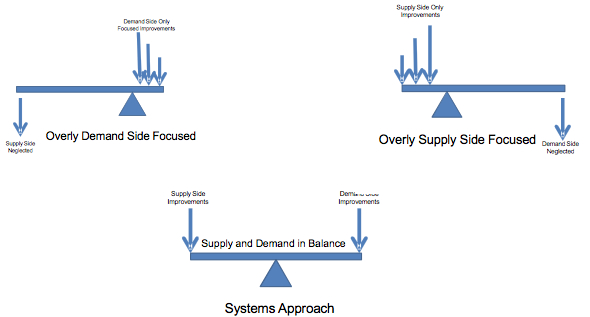

When you take a systems approach you can see that to maximize efficiency the focus and effort must be balanced between the supply and demand sides. For peak efficiency, you must produce air most efficiently, but you must also conserve and use it most efficiently. In a real balance if you move the fulcrum or focus point too far to one side or the other, it requires significantly more effort on that side to reach a balance. If you focus all your efforts on only one side (supply or demand), at first you may achieve reasonably good results, but it will become more and more difficult and will require expending more and more capital and human resources to keep improving. A much smaller effort and investment on the other side may result in huge savings.

For more information, please visit www.compressedairchallenge.org.